There was a time when “Made in America” adorned the hulls of warships that dominated the oceans. Now, that steel pride has rusted into a logistical liability. In 2025, the U.S. quietly accepted a bitter truth: it cannot outbuild China alone. With China controlling up to 65% of global shipbuilding output and rapidly churning out a navy that dwarfs the Pentagon’s projections, America’s naval superiority has become a memory.

Enter the doctrine of Maritime Statecraft, a pivot away from industrial autarky. Instead of trying to rebuild domestic capacity from scratch, the U.S. is outsourcing naval muscle to allied shipyards. Under the “Make American Shipbuilding Great Again” (MASGA) initiative, partners like South Korea, Japan, and Finland are being tapped to fill the gaps and in some cases, replace entire segments of U.S. production.

The most aggressive mover is Hanwha Ocean, which bought the Philadelphia Shipyard for $100 million and committed another $5 billion to retrofit it with “smart yard” technologies automated welding, digital twin modelling, and rapid hull assembly. The target: from one ship per year to twenty.

Meanwhile, HD Hyundai is supplying the U.S. Navy with modular logistics vessel designs. American yards will assemble these ships from South Korean-made blocks a strategy that slashes timelines and complies with domestic laws by keeping final assembly stateside.

It’s not all future tense, either. Ships like the USNS Wally Schirra have already undergone maintenance in Korean shipyards at less than half the time it would’ve taken in the U.S. This shift lets the Navy redeploy faster without building new hulls an operational cheat code.

Why U.S. Yards Fell Behind

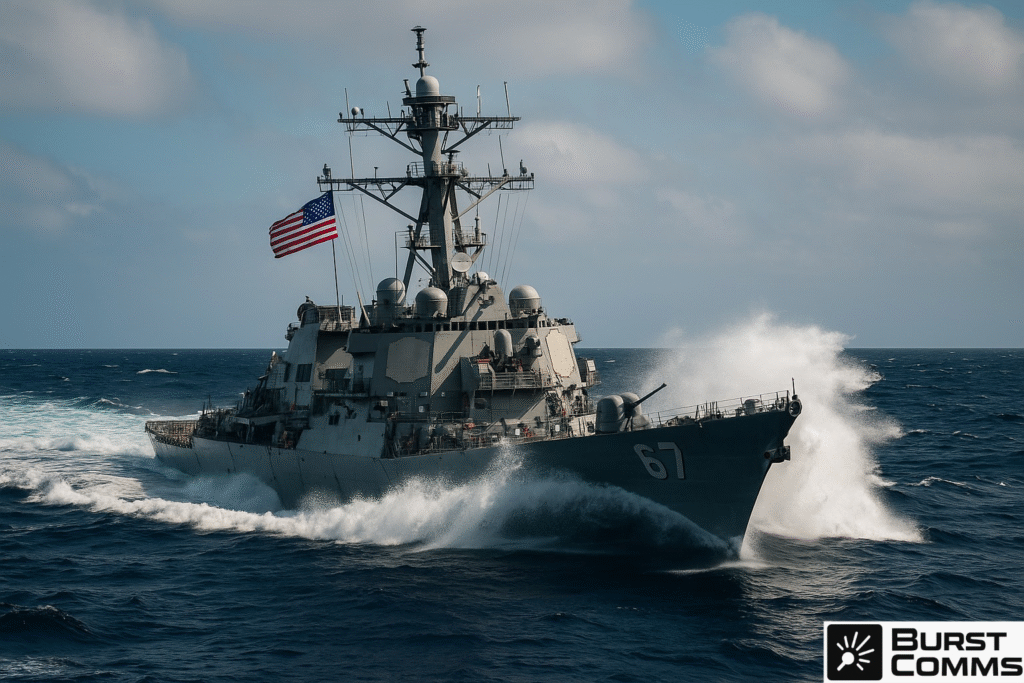

This pivot didn’t come out of nowhere. U.S. naval shipbuilding has been on bureaucratic life support for decades. A single Arleigh Burke-class destroyer now costs around $2.5 billion and takes 28 to 36 months to build sometimes longer when you account for endless redesigns, system change orders, and late-stage rework. The Constellation-class frigate programme meant to be a “simple” adaptation of a proven Italian design was so riddled with delays and technical errors that construction was halted after four hulls. The first ship won’t arrive until 2029, at double the intended cost.

Why? Because U.S. yards are still stuck in Shipbuilding 1.0. Design models often launch at 70% completion. Manual welding and inspection dominate. Every minor variation becomes a costly engineering snowball. According to the GAO, many ships are technically incomplete when accepted and finish construction after delivery.

Compare that to South Korea’s smart yards, where Siemens’ digital twin systems simulate the entire production sequence before the first weld is made. Spider bots paint and blast hulls. Automated gantries execute welds with micron-level precision. An Aegis destroyer rolls out in 18 months, not because they work harder but because their tools are smarter.

But this isn’t just an outsourcing story. It’s an industrial intervention. The presence of Hanwha, Hyundai, and Japanese component suppliers on American soil introduces real market pressure into a stagnant duopoly of U.S. defence primes. And it mirrors what companies like Anduril are already doing: dragging legacy contractors kicking and screaming into the 21st century.

Anduril didn’t just build autonomous defence platforms. It broke the rules of the game. Fast iterations. AI-first systems. Modular designs. The message was: deliver better, faster, cheaper or we will. Now, that same message is aimed at shipbuilders.

Hanwha’s Philly yard isn’t just building ships. It’s establishing a performance benchmark. If it can produce comparable hulls faster and cheaper with smart automation, it exposes exactly how bloated, antiquated, and overpriced the traditional U.S. yards have become. It also opens the door for price competition, tech transfer, and modular methods to become default not exceptions.

In other words: these foreign partnerships might succeed not just by adding capacity, but by forcing reform. By breaking the monopoly of complacent legacy players.

Japan’s contribution focuses on precision engineering and high-tech components. A 2025 agreement allows Japanese manufacturers to supply core propulsion systems, pumps, and generators to U.S. ships. There’s also movement on reviving railgun technology a potential countermeasure to Chinese hypersonics based on successful Japanese trials.

Then there’s the Arctic. The U.S. Coast Guard’s icebreaker programme was on life support until a trilateral agreement with Finland and Canada broke the deadlock. Four Finnish-built icebreakers are being purchased outright something that required a presidential waiver of longstanding procurement laws. The rest will be built in the U.S. with Finnish tech a workaround that saves time while rebuilding lost capability.

Second Cold War, or 1930s Replay?

So is this Cold War 2.0 or something darker? In the 1930s, Western democracies delayed rearmament while fascist regimes built arsenals. Today, China isn’t hiding its naval ambitions. It’s building, deploying, and daring the U.S. to blink.

If the U.S. alliance network can rapidly industrialise across borders, it might just stabilise the naval balance of power. If it can’t or if protectionist backlash and bureaucratic inertia win then the seas of the 2030s might look a lot more like those of the late 1930s than anyone wants to admit.