TLDR Highlights

The 2012 Turning Point: Global well-being shifted significantly around 2012, as the combination of smartphone saturation and engagement-based algorithms moved the internet from a "utility of well-being" to a "psychotoxin".

The Outrage Economy: Digital platforms are economically incentivised to prioritise moral outrage, with internal data showing algorithms weighted "anger" reactions 5x more than standard likes to keep users engaged.

Mean World Syndrome: Constant exposure to global tragedies through a "zero-friction" digital window distorts our perception of reality, making the world seem far more dangerous than it statistically is.

The Digital Panopticon: Total digital visibility has eroded our private "interiority," leading to widespread self-censorship and "performative virtue" as users seek to avoid algorithmic or social "cancellation".

Cognitive Atrophy: By outsourcing memory, navigation, and social coordination to apps, we are witnessing a decline in cognitive resilience and a loss of traditional problem-solving skills.

The Analog Resistance: A counter-movement is rising; 2025 saw a 25% surge in "dumbphone" sales as younger generations attempt to reclaim "radical presence" and the right to be bored.

Some of us are old enough to remember the first iPhone being released, the first smartphone, for that matter (it wasn’t an iPhone). I also personally recall reminding myself that I needed to get on that “internet thing” and see what it was about. From memory, I was somewhat late to that game as I simply didn’t see a need for it when it was initially popping off. Life was full enough for me back then, hanging out with my mates, going to parties, and drinking more than a single human should. The internet was being talked about a lot, but somehow, I felt like it could wait; I had enough on my plate. Looking back at those days, something singular stands out for me: I was busy “doing” things in person and life was fuller.

Now you might be thinking that was to be expected, younger people are out more often and are naturally living life with more energy. Well, yes and no.

When I venture out into the big, bad offline world, I can’t help but soak up what I see and compare it to what I have seen before. Today, I most commonly notice how “absent” young people appear to be, as well as how unsure they appear when alone. This isn’t just a Western thing, either; I have noticed it in Shanghai as well as the UK and USA. I recall my initial days living in Shanghai, taking the metro to work, and as I stood there looking around me, I noticed something. Every single person had a smartphone in front of their faces and they were peering into it like it was a drip-feed of sustenance, a drug that they craved.

I started to see patterns. Whenever people were moving, they were generally looking straight ahead, interacting with the wider environment just enough to avoid falling over. However, upon any instance of stopping and standing still, almost universally, the hand began to reach downward to retrieve the phone. I felt like people had evolved to treat their phones as a sort of shield from the boredom or loneliness of the world. However, I came to realise it was something else entirely. People had become addicted to the feeling of controlling their worlds, and the phone was a window into that little bubble they peered into.

I thought it was akin to seeing swimmers swim, moving faster under the water, and yet biology demanded they take a breath regularly in order not to drown. Whilst sitting and having a coffee on a busy Shanghai street in the former French Concession area, I would people-watch for 30 minutes or so. The swimmer analogy was solidifying in my mind: people were moving fast, navigating through the medium of life, but at regular intervals, they needed to breathe. At traffic lights, crosswalks, even in queues at shops, they would take a deep breath, absorb their own bubble, and then resume moving. Why had we arrived at this new form of existence, I thought? Well, that was a much harder question to figure out.

I think I’ve figured it out.

Performance Enhancer to Addictive Dependency

When the internet first arrived on the scene, it was new, untapped, exciting, and full of potential. Chat apps like MSN and ICQ popped up and allowed us to reach people we would never have met otherwise. Information was now at our disposal; we no longer needed to go to libraries to access information, it was there for everyone.

The downside to all of this was that we could now be met by people we might not have wanted to meet. Information that might be detrimental to our lives or wellbeing was now readily available, and “learning” became an esport. We no longer “know” things as we once did (like phone numbers) we simply know where to find them now.

Chatrooms were full of people from across the world, some good, some not so good. Kids could talk with adults like never before, and games moved from a mostly solitary affair to a multiplayer society. We now had people entering our lives in ways that we had little experience managing; it was full of energy and ultra-stimulating at first. Information, activities, and data began to flow into our daily lives at unprecedented levels. Like a house party where some are invited and others just turned up, the internet changed our social circles from relatively solid into something new. We began to lose control of the sizes and nature of our social networks, and that had consequences.

The Rising Tide

From the golden days of the late 1990s up until around 2011, the internet was seen as a digital “utility of well-being”. However, after 2012, it began to devolve into a “psychotoxin”.

Around 2012, the convergence of high-speed 4G data and the saturation of the smartphone market meant that the house party was firmly in everyone’s pockets 24/7. From personal experience, a party can lose its appeal when it appears too big and full of strangers.

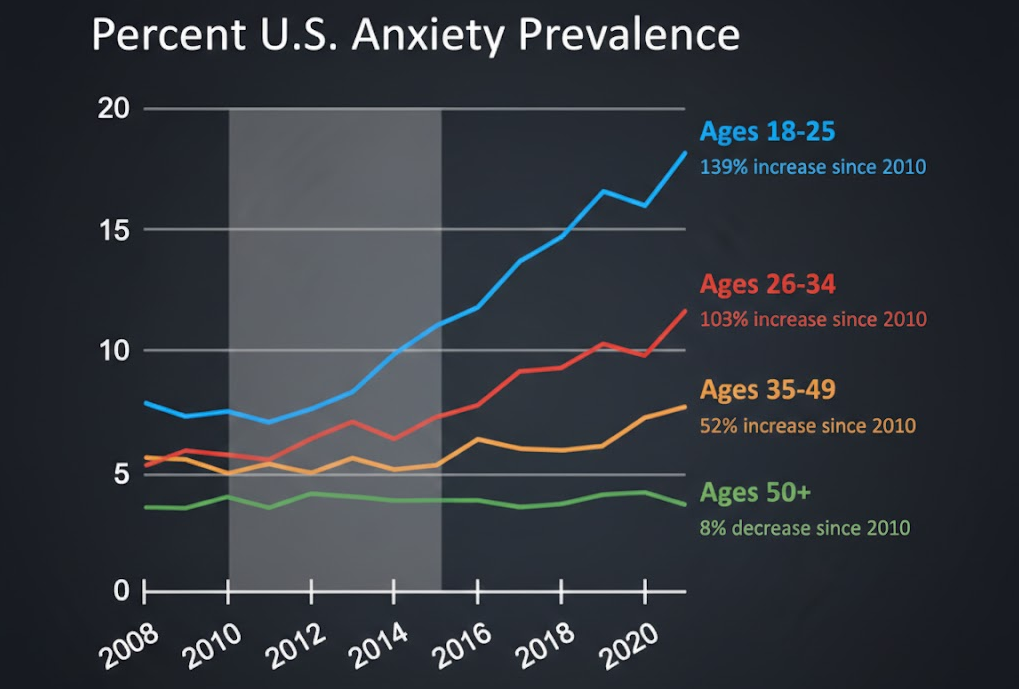

Algorithms began to tweak what we saw, moving away from what our friends were looking at to instead showing us things that “maximized engagement”. Gradually, our feeds started to become more of a source of shock and awe and less of a catch-up with friends. Around the same period, these shifts coincided with a sharp, unprecedented decline in adolescent mental health. In English-speaking countries alone, self-harm rates that had been improving or stable since the 1990s skyrocketed shortly after this shift.

Mean World Syndrome

With algorithms increasingly targeting anything that gets engagement, users found their digital window an increasing source of bad news. The interesting thing about this aspect is that before this occurred, we had grown to regard the same devices as sources of happiness. The learned behaviors now ingrained became the ideal entry point for negative data to enter our worlds. We did not, however, identify the change; instead, we simply kept on peering through the window, but the picture got less beautiful.

We entered into a world of “statistical distortion,” where every citizen is now a pseudo-journalist and every unfortunate event is shared. Combine this with an algorithm that actively prioritises outrage, and you get the perfect storm. The world looks increasingly volatile and unstable, with every tragedy shared globally within minutes.

Our devices became the source of, and the solution to, our increasing anxieties. We sought refuge in the things we like and find comforting, things that provide a sense of control and perhaps even a hit of dopamine. However, the same devices are constantly serving us news items or events that cause us stress. Our raised cortisol levels ironically leave us more anxious than before we looked, and the cycle continues endlessly.

When I observed people unconsciously reaching for their phones the moment they came to a stop, it was this mechanism playing out. The brain, detecting heightened cortisol levels, sought to offset it with some dopamine, and so the cycle repeats. The unequal balance of reassurance (illusions of control) delivered alongside negative stimuli that grab our attention is by design. We spend more time engaged with the source, and so the engagement is rewarded by more of the same. I recall the movie Limitless when I think of this balance: a drug that enhances us to new levels initially, but subsequently becomes our undoing unless it is maintained at ever-increasing dosages.

We are hooked in a spiral of dependency.

The Digital Panopticon

Just like with any addictive substance, our behaviors were modified around its key mechanisms. The internet and our interactions within it have created a digital prison where inmates are never sure if they are being observed. Younger people who grew up in the internet age have known no other interaction model, and so their behaviors are the ones most vulnerable to its effects.

When I noticed the sense of unsureness about young people when they are alone or out of their social safety net, it was this in action. For humans to be authentically happy, we need a “backstage area” where we are permitted to be weird or try out ideas without fear of judgment. In today’s world of total visibility, this area has been eroded, and young people cannot easily develop an authentic self. The sense of all aspects of life being online created a sense of always performing for the invisible watchers.

There is a striking sense of self-censorship in today’s world where the idea of speaking out of line is unthinkable. Users have grown up with search history, location, and posts all being recorded forever, and so behaviors are shaped to avoid “cancellation”.

This also creates another problem we see a lot of today: “performative virtue.” The accepted status quo of knowledge (the tower) produces followers who act and think in a way that is in line with the majority viewpoint. Disagreement is permitted only against sanctioned subjects; if a rejection of a non-sanctioned subject occurs, the actor is in turn labeled as an outsider. The effect of this performative virtue is to suppress any budding sense of being different as a “defect” from the collective view.

By relying on outsourced centers for our identity, our character, and our sense of self-regulation, our brains are witnessing significant atrophy in cognitive resilience. Recently, a younger relative of mine had an issue with her PC which cut her off from her regular online sources of interaction. The displayed level of distress was disproportionate to the situation. However, in today’s world, this is a common occurrence. In many cases, younger people have lost the old mechanisms of patience and problem-solving due to persistent exposure to instant gratification.

Learning to Swim

As we enter 2026, there is actually a glimmer of hope that things are finally changing for the better. Just as everything has a lifespan, so too is this true for the internet age as we know it.

Data suggests that users are increasingly getting tired of the current internet and its interaction models. Throughout history, each generation shrugs off some key areas of the traditions of their parents, and a social shift occurs. What we are seeing today is that very phenomenon in action again.

Take, for example, the sales of “dumbphones.” In 2025, sales of such devices surged 25%, specifically driven by Gen Z. Being disconnected appears to be shifting from a fringe lifestyle to a status symbol. Groups such as “The Luddite Club” are now promoting “Appstinence,” valuing face-to-face communication over digital. Trust in the digital world is faltering alongside such movements because so much of what we say and do is recorded, analysed, and monetised.

As we move towards 2030, the battle for privacy is moving from what you do to what you think. Device makers are now actively seeking to integrate with the human brain, potentially opening up access to our desires and biases. Such developments are being received with caution by the younger generation, and rightly so. However, these devices will almost certainly be marketed as medical solutions at first, only being offered as “upgrades” later on.

The Right to be Unstimulated

We have seemingly spent the last 30 years attempting to predict all aspects of life. Our buying habits, our political and social views, and even our secrets are now tracked, especially with the advent of AI. Our worlds are being shaped by “intent” and how best this can be mined for commercial gain.

Perhaps the reason why so many people today are addicted to the diminishing returns of dopamine from their devices is because we are somehow aware of this scrutiny. The hope is that the younger generation is now realising that serendipity is the path to a fuller sense of authentic happiness. The right to experience life without trying to predict it as accurately as possible. To hold conversations with other people that might say things you don’t currently think.

From my experience, some of the most memorable moments in my life have come from unexpected encounters. Life is utterly devoid of the joy of overcoming challenges if everyone says the same things and thinks the same way.

So maybe next time you find yourself standing in line waiting for your next flat white, if you feel your hand reaching for the dopamine machine, maybe resist it just this once. Maybe see what happens when you watch life happening in front of you instead of the illusion of control given to us by the tiny screen.

You might even do something unpredicted.