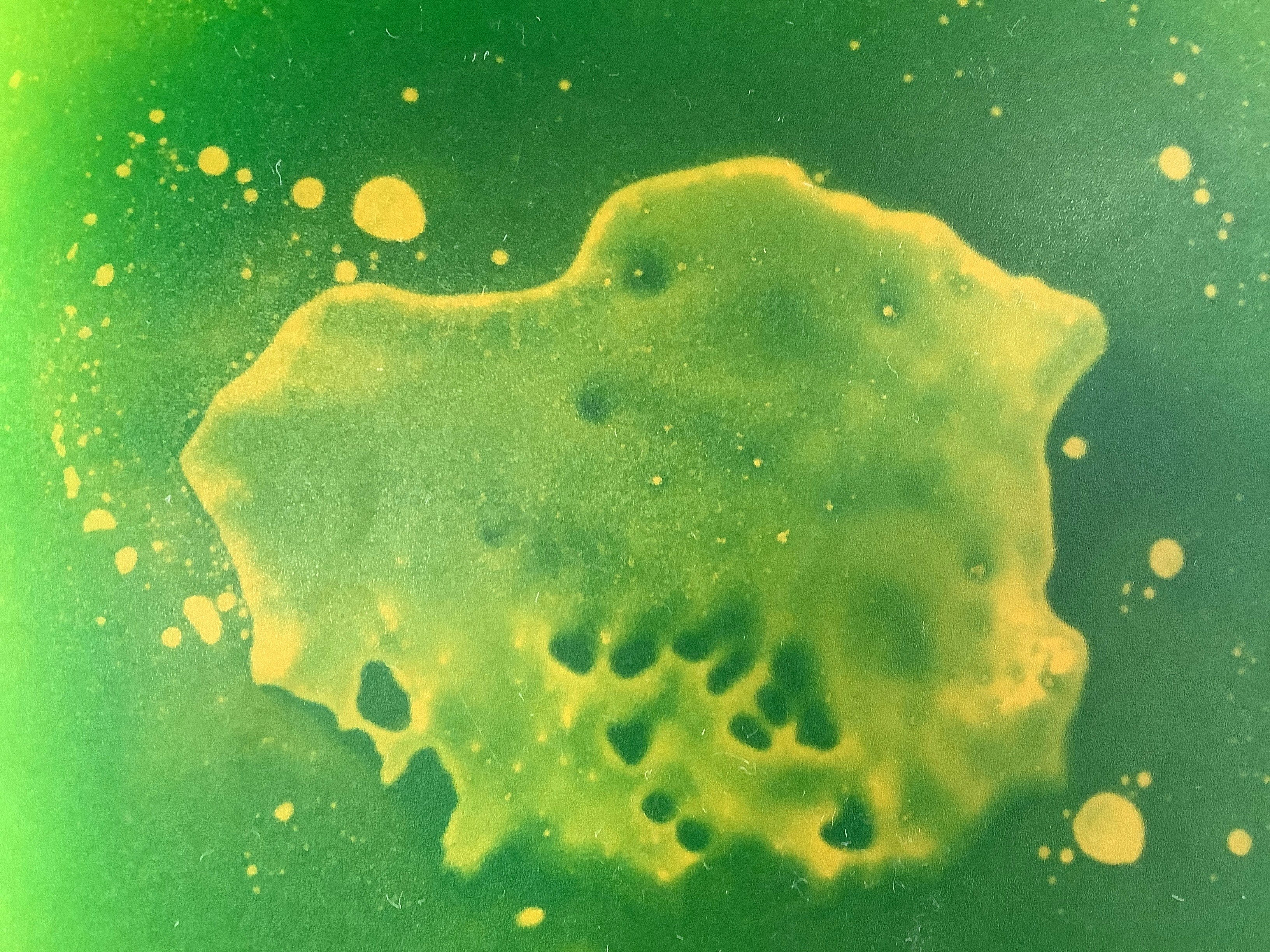

If you ever need a reminder that humans are not quite as clever as we like to think, consider slime mould. It is not a plant, not an animal, not even a fungus. It is a shapeless yellow blob, technically a single cell, that manages to behave like a distributed intelligence system without the faintest trace of a brain. Somewhere between spilled custard and sentient porridge, slime mould quietly undermines the idea that neurons are the only path to cleverness.

One of the most famous experiments involved giving the mould a map of Tokyo. Researchers placed oat flakes where major centres sat and left the slime to wander. Within hours it had produced a network of tubes that looked eerily like the Tokyo railway system, optimising efficiency and redundancy in almost the same way that human engineers did with computers, decades of experience and piles of spreadsheets. To make it worse, slime mould has been known to outperform some algorithms at finding the shortest path through a maze. Imagine a single blob, growing on damp paper, casually shaming your GPS.

What unsettles scientists is that it also appears to have memory. Not the Netflix password kind of memory but something stranger. When researchers exposed it to unpleasant substances like caffeine, it learned to avoid them. After repeated exposure it eventually adapted, crossing those areas as if it had worked out that caffeine was annoying but not fatal. Even more puzzling, if two moulds fuse, one can share the learned behaviour with the other. No neurons, no synapses, yet knowledge is transferred. That is the kind of detail that makes biologists stare out of windows and reconsider their career choices.

The implications are uncomfortable. If something with no brain can learn, remember, plan and share information, perhaps intelligence is not tied to grey matter at all. Maybe it emerges wherever a system is complex enough to process feedback, whether that is slime crawling across agar, ants building colonies, or data packets moving across the internet. It suggests that intelligence could be a property of systems, not just creatures. That idea keeps creeping into AI research too, where distributed machine networks are designed to learn without central control. In a strange way, the slime mould got there first.

There is also the philosophical insult. Humans like to imagine we are the crown of evolution, but the blob’s ability to adapt to hostile conditions, optimise networks and survive for millions of years without fuss makes us look like the overcomplicated experiment. Our achievements include smartphones, TikTok dances and nuclear weapons. Theirs include immortality, resilience and putting Japanese rail engineers to shame.

Science still cannot fully explain how this works. The leading idea is that the mould’s branching tubes naturally shift to optimise fluid flow, essentially performing computation through growth. But that explanation feels thin when you see it remember past encounters or reconfigure itself after being cut in half. It is not supposed to have purpose, yet it behaves as though it does.

If we measure intelligence only by test scores and human reasoning, slime mould is nothing. If we measure it by adaptability, efficiency and problem solving, it is arguably more impressive than us. The uncomfortable possibility is that intelligence is everywhere, not just locked in skulls. If that is true, then the line between mindless matter and conscious life is not a line at all but a messy spectrum with a yellow blob wandering across it.

So next time your train is delayed, consider this. Somewhere, on a forgotten petri dish, a brainless puddle worked out a better timetable than the rail company you pay each month.