TLDR Highlights

The Glitch: Stephen Chase, a 33-year-old from Utah, wakes up from every surgery speaking fluent Spanish despite having no conscious mastery of the language.

The "Database": While he isn't a native speaker, his brain "archived" the rhythm and sounds of Spanish from childhood neighbours (the Osmosis Factor) and a later two-year mission in Chile.

The Chemical Key: Anaesthetics like Propofol and Sevoflurane temporarily "switch off" the brain’s monitor (the Prefrontal Cortex) that usually keeps English dominant.

The 60-Minute Window: For a brief period as the drugs wear off, the brain's language switch gets stuck, allowing latent, "uninhibited" Spanish to flow out with native-level speed and zero fear of making mistakes.

The Big Question: If our minds are constantly recording data we can't access, what else is "archived" in our subconscious, and are we truly the masters of our own mental "software"?

Ever want to learn another language but don’t seem to have the time or the ability to see it through? Yeah me too, I have a mate who speaks Chinese fluently and learned it at a frankly annoying pace. Jealousy aside, time is usually the biggest obstacle for anyone learning a language but some people, some lucky few don’t have that issue.

Take for example, Stephen Chase, a 33-year-old from Utah who looks to have found a glitch in the Matrix. Stephen went viral recently when a video of him speaking post-surgery showed him speaking exclusively native-level Spanish to hospital staff.

The strange part was that this “switched state” typically lasts between 20 to 60 minutes before his English returns and his Spanish proficiency fades away. He also appears to have no memory of the event as a consequence of the amnesic effects of the anaesthetic wearing off.

Even more weirdly, Chase had a history of this behaviour occurring each time he ever had surgery. With a history of sports-related surgical procedures, Chase began to exhibit this “miraculous” response each time he awoke, so much so that he would warn staff beforehand.

History Of Language Acquisition

Some of the media portrayed this as a miracle event where a man learned Spanish overnight; however, there’s more to it than that. Chase grew up in Salt Lake City and spent a lot of his childhood at a friend’s house whose parents spoke Spanish. Whilst he didn’t understand the language they spoke, his brain did appear to achieve the prosody (rhythm and intonation) of the language.

Additionally, as a young adult, Chase spent two years on a religious mission in Chile. The assumption is that during this period, Chase’s brain adapted to the total immersion and his understanding moved from book-learned to procedural memory. The reason this is important is that procedural memory is responsible for our autopilot skills, such as how to ride a bike, etc. Potentially, Chase’s brain learned elements of Spanish without him being consciously aware and the information remained latent in his memory.

Predictable recurrence

Given that Chase came to experience this strange event multiple times, he began to warn staff before each procedure. Experts believe that this alone may have primed his brain in a manner that activated the Spanish when he awoke.

Looking into the science of this phenomenon, there are some interesting factors at play that might explain the outcome.

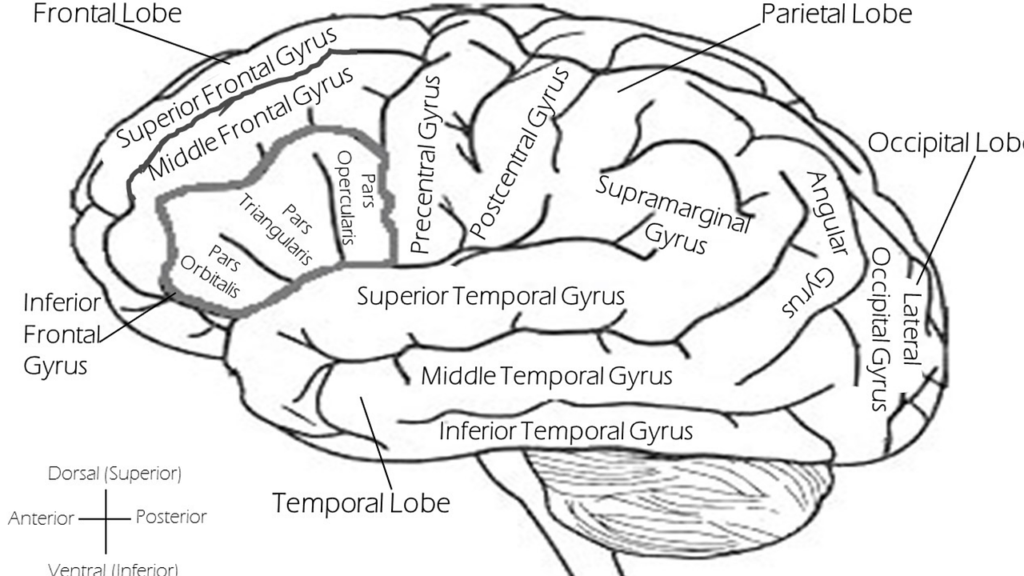

The drug used, Propofol, suppresses the part of the brain (the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex) that usually acts as a system’s “monitor”. In waking life, this monitor keeps his English front and centre and his Spanish remains inhibited. However, when the monitor is “asleep” due to the effect of Propofol, this inhibition is not present and the Spanish flows out uninhibited for a time.

We have all seen the funny videos of people waking from surgery, saying things to their loved ones that they might later blush about. Well, the effect here is due to the Sevoflurane clearing the system, which creates the 20 to 60-minute window of cognitive dissociation. Effectively, the brain is “awake”; however, the language switch (likely the Left Caudate Nucleus) is in the wrong position.

In terms of how his native-like level of pronunciation came about, it is thought that the drugs remove the element of fear. For anyone that has learned a foreign language, the fear factor of making mistakes is one of the biggest hurdles to overcome. Without this limiting factor in place, Chase simply had no hesitation and appeared to access those childhood rhythmic templates to speak with the rapid cadence of a native Spanish speaker.

What’s hiding inside us all?

The story of Chase is a truly strange one; however, it does raise a very real question about the human mind. Given this single example shows us the capacity for us all to be holding information in our minds, what else could remain untapped in there?

With the advent of increasing gains in neurology, assisted by AI-augmented research, are there more discoveries around the corner like this one? Could we one day learn how to remove further inhibitors that offer us access to more untapped potential of the human brain? The question is, why does biology place these inhibitors there in the first place, and what is our potential limiting us from or protecting us from?

I suppose a truly uninhibited human mind comes with downsides (I have seen drunk friends fail spectacularly when in such states) but a selective approach might be the key. The other side of the coin could be that our mind holds the keys to certain data for our own good; the question is then, are we our own jailor and prisoner?

Perhaps that’s a Pandora’s box we should leave closed for our own good.