In the old days, propaganda took effort. You had to find journalists willing to pretend the script was their idea, slip them some funding, and maybe a medal if things went really well. The CIA’s Operation Mockingbird was exactly that kind of vintage manipulation, dozens of reporters secretly tied to the agency, a few hundred more sympathetic, and suddenly the country saw exactly what it was meant to see. The Church Committee later confirmed the relationships in 1975, exposing how at least fifty journalists had direct CIA links, while Carl Bernstein estimated it was closer to four hundred.

Back then, America’s media was tiny, three TV networks, a few powerful papers, and an audience that mostly trusted them. Control the editors, and you controlled the story. Elegant, efficient, morally bankrupt.

Today, you don’t need spies or envelopes of cash.

The gatekeeper is an algorithm.

It doesn’t smoke in backrooms or meet handlers in cafés. It hums quietly in your pocket, deciding what breathes and what suffocates. It knows outrage keeps the lights on and that calm people don’t click. So it feeds you outrage. All day. Every day. Because that’s the business model, not state control, but structural compulsion.

Researchers now talk about algorithmic radicalisation, the process where recommendation engines push users toward more extreme and emotionally charged content to maximise engagement. One study found that divisive, anger-driven material spreads significantly faster and more widely than factual reporting (PMC analysis). Another describes how filter bubbles isolate users into narrow ideological loops, creating tailor-made worlds that feel real but aren’t.

So the propaganda doesn’t need intent anymore, just data.

Somewhere around 2011, the mask slipped. The trigger was Occupy Wall Street.

For a brief moment, people looked in the same direction, up. The protesters in Zuccotti Park weren’t divided by ideology; they were united by class. They pointed at the machinery behind the curtain: deregulation, monopolies, and the political capture of finance. They were, in short, correct.

And then, somehow, the conversation changed.

By 2012, the media had moved on from money to morality. The word “inequality” gave way to “identity.” The phrase “we are the 99%” splintered into competing hashtags. The data shows it clearly, after 2011, the use of terms like “racism,” “white supremacy,” and “people of colour” exploded across the American press. Class was out. Culture was in.

This wasn’t random. Around the same time, the advertising model collapsed. Publications desperate for revenue pivoted to digital subscriptions, and subscriptions depend on keeping readers emotionally charged. Anger pays. Consensus does not.

The report calls this the political economy of indignation, a polite way of saying outrage became a product line. It wasn’t some editorial choice; it was a survival mechanism. Newsrooms realised that moral panic converted better than balance, and the market agreed.

By 2016, the industry had perfected it. One half of the country was told democracy was under fascist assault; the other, that socialism was devouring the republic. Both sides clicked. Both sides paid. Neither noticed the strings.

Meanwhile, look at who owns the megaphones. Comcast, News Corp, and Warner Bros Discovery, massive, diversified conglomerates whose profits depend on the same markets Occupy wanted to dismantle. Comcast is a regulated utility provider reliant on government favour (Comcast filings). News Corp makes its money through Dow Jones, a brand that literally profits from stable financial markets (IBISWorld profile).

If anti-capitalist reforms ever took hold, their share prices would be first in line for a haircut. So the system did what systems do, it defended itself.

It didn’t need censorship or conspiracy; it just needed incentives. Turn the spotlight away from economics and onto identity. Keep the population arguing about the symptoms, and they’ll never treat the disease.

This is how Mockingbird evolved. The old model used infiltration, a handful of editors and columnists. The new one uses algorithms. It’s cleaner, faster, and infinite in scale. The Cold War propagandists could only dream of a system where the public not only consumes propaganda but helps train it.

Social media finished the job. Platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Facebook run on recommender systems that feed users whatever keeps them emotionally active. The Observer Research Foundation described how extremist and hyper-partisan material consistently outranks balanced reporting. Engagement isn’t just measured, it’s engineered.

False or polarising content now generates entire economies of attention. The Carter Center calls it the disinformation economy, a landscape where misinformation earns hundreds of millions in ad revenue annually, creating a business incentive to distort reality.

So the control function that once required covert funding now runs on automatic billing. The propaganda writes itself.

When stories vanish from trending lists or movements evaporate online, there’s no editor to blame, just the code doing what it’s built to do. The Potomac Institute calls this shift “the transition from gatekeeping to algorithmic amplification” (Potomac report). The algorithm isn’t political; it’s indifferent. But its logic, amplifying whatever divides, serves power better than any secret directive.

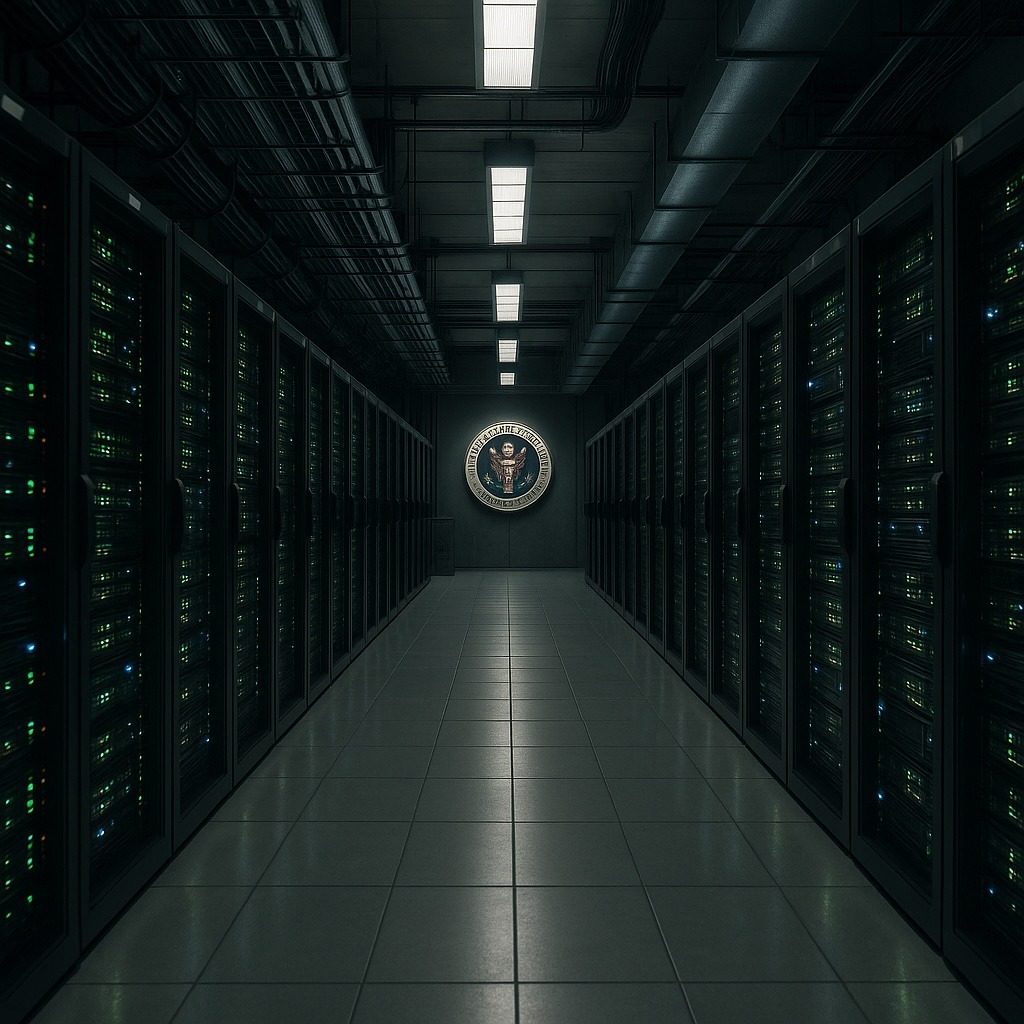

Mockingbird was about who controlled the newsroom. Its descendant is about who controls the plumbing. The pipes of the information age, the feeds, the search results, the trending bars, are now the battlefield. And no one needs to infiltrate them because we willingly built them, maintain them, and live inside them.

That’s the brilliance of Mockingbird 2.0. It’s self-sustaining, self-optimising, and invisible.

The Cold-War propagandists would be horrified by how efficient their legacy became. No secrecy. No oversight. Just perfect automation. And the punchline? We trained it. Every click is consent. Every share is unpaid labour for a system that monetises division and calls it engagement.

The old Mockingbird was a whisper campaign.

This one hums through every data centre on Earth.

It doesn’t need journalists on the payroll. It’s got all of us.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article represent analysis and opinion based on publicly available data, academic research, and media sources. They are not statements of fact about any individual or organisation, nor do they allege wrongdoing. BurstComms publishes independent commentary for informational and discussion purposes only. Readers are encouraged to review cited materials and form their own conclusions.