If you take the global economy at face value in 2025, you might think we’ve made it through the storm. Growth sits at roughly 3 percent, inflation is drifting lower, and the headlines sound relieved, almost triumphant. The message is simple: the “soft landing” happened, the worst is over, and the world can finally exhale.

Except none of that is true.

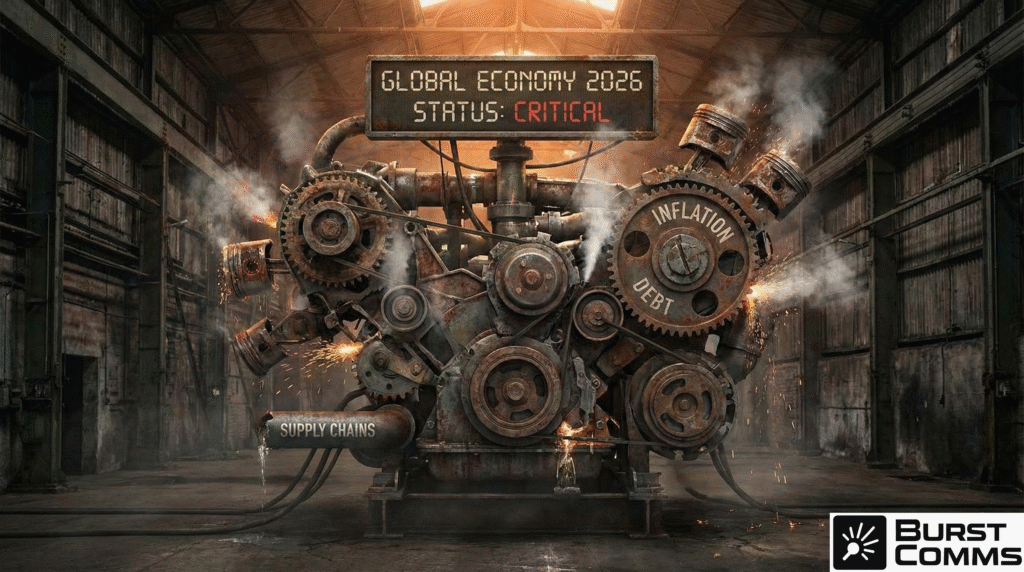

Beneath the tidy averages, the global system resembles a cracked porcelain bowl held together by surface tension alone. The synchronised world of the early 2000s, where supply chains ran like clockwork and capital flowed with the innocence of a pre-weaponised trade era, has dissolved into something far more precarious.

The defining feature of 2025 isn’t calm.

It’s stable instability.

The numbers look fine because they hide the fractures.

America: the booming engine running on borrowed oxygen

The United States heads into 2025 with the sort of swagger usually reserved for economies half its age. Growth north of 2 percent, relentless consumer spending, and a corporate sector pouring billions into the AI build-out. Data centres multiply like mould, and semiconductor demand is fuelled by every company trying to catch the next AI productivity wave.

But the roar of the US economy echoes inside an increasingly fragile structure. The national debt blasting through $37 trillion is not just a number, it’s a gravitational force. With Treasury yields hovering around 4.4–4.8 percent, interest payments are quietly eating the budget alive. The country remains the strongest of the advanced economies, but it does so by leaning ever harder on fiscal steroids.

It works, until it doesn’t.

And that’s the American story going into 2026: a machine that still outruns the world but increasingly feels the strain in its chassis. Whether that strain snaps into something ugly depends on how the country navigates an approaching refinancing cliff that analysts from Visual Capitalist and the IMF are already waving red flags over.

China: slowing on purpose, expanding by stealth

China’s headline growth, 4 to 4.5 percent, may look like a slowdown, but it’s actually camouflage. Beijing is dismantling its old growth model, letting the real-estate bubble deflate, and betting everything on the “New Three”: EVs, solar, and lithium batteries.

The strategy is brutal but intentional.

Domestic consumption is weak, youth unemployment is corrosive, and the property sector has been ritually sacrificed. But China is making up for the shortfall by pumping industrial output and exporting the excess. If domestic consumers won’t buy, the world will.

And here’s the part that matters most for 2026: Western inbound investment collapses, but China’s outbound investment surges, flowing into Vietnam, Mexico, and Hungary. It is the same playbook Japanese firms used in the 1980s, shift production abroad, bypass tariffs, keep market access, and call it global expansion.

Vietnam becomes an assembly extension of Guangdong. Mexico becomes a free-trade backdoor into the United States thanks to USMCA access. Hungary becomes China’s industrial embassy inside the EU.

Nobody has decoupled.

China has just changed the return address.

Europe: a quiet crisis with no good exits

Europe feels strangely calm only because the cracks run deep enough that most people have stopped looking down. The southern economies, Spain, Portugal, Greece, enjoy a brief revival through tourism and EU recovery funds. But the centre of gravity, Germany, is struggling to remember what industrial strength feels like.

With growth forecast near 0.2 percent, Germany is now forced to confront an uncomfortable truth: its competitiveness relied on cheap Russian energy and a hungry Chinese market. Both vanished. Its once-invincible auto sector is losing global share to Chinese EV manufacturers whose mastery of battery tech and vertical integration borders on unfair advantage. Even the European Commission’s own country forecast sounds like a doctor avoiding eye contact.

Across the Channel, the UK is healing from recession but still limps forward on anaemic productivity and persistently high inflation. Services keep the country alive. Everything else needs resuscitation.

Europe moves into 2026 with the fragility of a crystal glass: intact, attractive, and one hard tap away from a spiderweb of fractures.

India: growth champion with a hollow foundation

No one can deny India’s momentum. Growth approaching 7 percent, rising consumption, a national tech stack that feels decades ahead of the West, and a reform agenda that finally seems to be paying dividends.

And yet, investors are quietly walking backwards out of the room.

For the first time in years, net FDI has turned negative.

Foreign companies are pulling profits rather than reinvesting, and Indian conglomerates are ploughing money abroad rather than at home. It’s not a crisis, but it does signal hesitation. The “China +1” strategy benefits India rhetorically, but in practice, most of the supply-chain relocations are flowing to Vietnam and Mexico, not Mumbai or Chennai.

India is rising, but its ascent is not yet anchored in global industrial reality. It is the world’s great growth story, but not yet its factory.

The Asian Tigers: where the world’s future supply chains are really forming

Japan, fresh off decades of deflation, is finally seeing wages rise, a generational shift supported by the Bank of Japan’s timid but symbolic policy tightening. South Korea is surfing the AI semiconductor boom, feeding Nvidia and every model that follows. ASEAN economies like Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia are becoming the world’s assembly line, absorbing industries fleeing China, while simultaneously absorbing Chinese capital itself.

This region doesn’t just benefit from fragmentation.

It is shaped by it.

The 2026 manufacturing map runs through Tokyo, Seoul, and Ho Chi Minh City far more than it does Berlin or Detroit.

Africa and South America: the world’s new treasure chests

If you want to see the future, follow the minerals.

Africa is becoming the core battleground for cobalt, lithium, copper, everything needed to electrify the planet. Chinese investment is accelerating at a pace that’s making Western policymakers wake up in a cold sweat when reading S&P Global’s mining reports.

South America isn’t far behind. Argentina’s mining exports are set to break records, lithium production is projected to soar, and Brazil is quietly positioning itself as a green-hydrogen powerhouse.

These regions are not merely resource suppliers.

They are strategic prizes in the next decade of industrial rivalry.

Where 2026 is heading

If 2025 is the year the world pretended everything was fine, 2026 is the year the façade begins to slip.

A wave of post-pandemic corporate debt matures just as interest rates remain painfully high. Trade tensions continue to escalate, with the United States openly contemplating universal tariffs, a move that would ignite retaliation across Asia and Europe. And China’s industrial overcapacity continues to push deflation into world markets, undermining manufacturers from Mexico to Malaysia.

Yet it’s not all doom. AI investments finally start delivering tangible productivity. Renewable energy becomes widely cheaper than fossil fuels. Central banks begin a slow return to sanity.

The world of 2026 isn’t collapsing, it’s reorganising. The age of hyper-globalisation is over the age of strategic globalisation has begun.

And in that world, the winners aren’t the cheapest.

They’re the ones that bend without breaking.