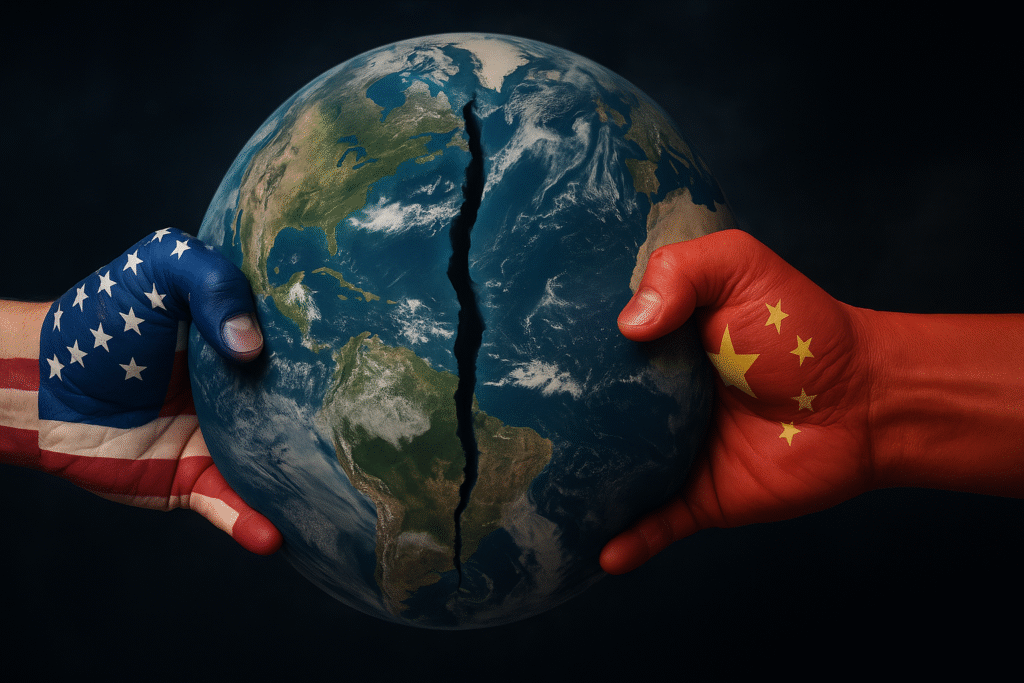

For three decades, globalisation was marketed as a bulwark against war. Entangled economies, shared dependencies, and mutually assured prosperity were supposed to make full-scale conflict irrational. It was elegant, seductive, and ultimately flawed.

The architecture of globalisation was not accidental. It was deliberately structured to create disincentives for war through the binding power of commerce. Nations that traded deeply with each other would be less likely to risk conflict, as any act of aggression would damage their own economic wellbeing. Capital, talent, and production were all to flow freely, forming a lattice of interlocking interests too costly to sever.

This design was institutionalised through the Washington Consensus, free trade agreements, global supply chains, and multinational legal frameworks. Even authoritarian states were welcomed into the fold, on the assumption that economic integration would moderate political behaviour. China’s accession to the WTO in 2001 was the apotheosis of this logic. If the most powerful autocracy could be embedded into the rules-based system, the system itself would be unbreakable.

But the model carried an unspoken vulnerability: it assumed all actors played by the same rules.

Enter the bad-faith participant.

China, paradoxically the nation that benefited most from globalisation’s open architecture, became the most strategic in exploiting its loopholes. It embraced global trade but resisted political liberalisation. It welcomed inbound investment but restricted access to its own markets. It participated in global finance while building parallel systems beyond Western reach. The result: an asymmetrical relationship where China reaped the gains of interdependence but never became meaningfully constrained by it.

This strategic ambivalence allowed it to become the manufacturing engine of the world, the rare earths gatekeeper, and a central node in countless Western supply chains. While Western firms pursued profit, Beijing pursued leverage. And when the political climate shifted, it held the stronger hand. By then, decoupling had become too painful to execute cleanly.

Russia, too, found ways to exploit the system’s assumptions. Its integration into European energy markets offered it insulation, not reform. The invasion of Ukraine showed that energy dependency created more deterrence for the consumer than the supplier. Sanctions were imposed, but rerouted trade and alternative buyers cushioned the blow.

So while the West assumed globalisation would civilise rogue states, the reality was more Darwinian. Bad-faith actors bent the system toward advantage, while liberal democracies remained trapped by their own economic orthodoxy.

Instead of a neutral, frictionless system, we’re left with what Henry Farrell and Abraham Newman call Weaponized Interdependence, a state where trade and finance become the very tools of coercion. Control the dollar clearing network, and you can freeze a nation’s lifeline. Control rare earth elements, and you can choke entire industries. Globalisation didn’t erase power politics. It gave them new wires to run through.

So, while the West talks of decoupling and the East quietly builds its own circuits, capital is no longer flowing for efficiency. It’s flowing for alignment. FDI within geopolitical blocs has become three times higher than investment between them. US companies are pulling out of China. Europe is scrambling to secure critical raw materials from anywhere but China. And global trade, once a rising tide, has been becalmed since 2016.

But despite the fragmentation, business remains the world’s last brake pedal. It doesn’t have the power to reverse course, but it can slow the descent. The lobbying power of multinationals, their reliance on Chinese markets, their exposure to global volatility, these keep governments from cutting ties too quickly. Chip bans get watered down. Sanctions find workarounds. Entire industries quietly ask for exceptions.

Still, this tension has limits. And the question we now face is whether there will be a point of no return where even business pragmatism can no longer hold the system together.

What would that look like? One sign would be a wholesale retreat of corporate players from rival markets. Not isolated exits, but sustained waves of divestment, triggered not by tariffs or regulations, but by geopolitical risk and reputational liability. When entire sectors begin to abandon operations in key economies, that’s when the glue of interdependence is truly giving way.

Another early warning: a marked reduction in expat workforces and high-level international placements. Multinationals often serve as informal bridges between cultures and systems. When executives no longer feel safe or see value in maintaining a presence abroad, the insulation against miscalculation thins.

We might also witness mass unwinding of cross-border supply chains in sectors previously thought unassailable, like pharma, aerospace, or finance. Not tweaks for resilience, but outright de-integration.

And then there’s the media. Would it report on this unravelling clearly? Unlikely. Most major media outlets are either owned or heavily influenced by conglomerates with deep commercial interests in preserving the appearance of stability. Would CNN run a segment titled “Wall Street Quietly Pulling Out of China” if its parent company depends on Chinese market access? Would the BBC call out UK industrial decoupling if its international partners include state-linked platforms? We already saw during COVID how supply chain failures were framed as temporary glitches, not systemic vulnerabilities. If this fragmentation deepens, expect it to be reported as a reshuffling, until it can no longer be hidden.

The evidence is already mounting. Apple is shifting supply out of China. Samsung is consolidating operations closer to home. US investment in Chinese manufacturing has cratered. Meanwhile, China’s own tech giants are retreating from Western capital markets, delisting and repatriating.

None of this means war is inevitable. But it does mean that the old belief, that capitalism makes the world safe, is dying. And what comes next is unlikely to be guided by spreadsheets. It will be driven by threat perceptions, resource control, and cold strategic calculus.

Globalisation wasn’t peace. It was a ceasefire built on mutual profit margins. And that ceasefire is ending.